Mexico: The Recent News

As a primer, the first thing you need to know about the Mexian oil industry is a single name: Petroleos Mexicanos, more commonly refereed to as PEMEX. Formed in 1938 via the expropriation of all foriegn oil entities by President Lazaro Cardenas, Pemex has had an effective monopoly on all matters oil & gas in Mexico since.

The Mexican senate passed, on Dec. 12, additional (to the 2008 amendments allowing third party service contracts) amendments to articles 25, 27, and 28 of the constitution which forbade private sector contracts and outlawed non-Mexican entities from the energy sector. While details on taxation, royalty, and the legal framework within which foreigners can enter the market are still to come, the immediate details appear to be a pretty radical turn away from historical norms.

What does all of this mean? Well let's start by taking a high level look at the oil situation in Mexico. Mexico's production is currently dominated by off-shore production (EIA estimated 1.9 million bopd or roughly three quarters of total production in 2011). The huge fall in production seen in the graph below came from the Cantarell which hit a secondary peak (utilizing nitrogren injection) production level of 2.1 million bopd in 2003, placing it as the second highest producing field in the world (behind Ghawar in the KSA), before entering into a steep decline phase. Current Cantarell production is 443,000. (A cautionary tale of decline rates!)

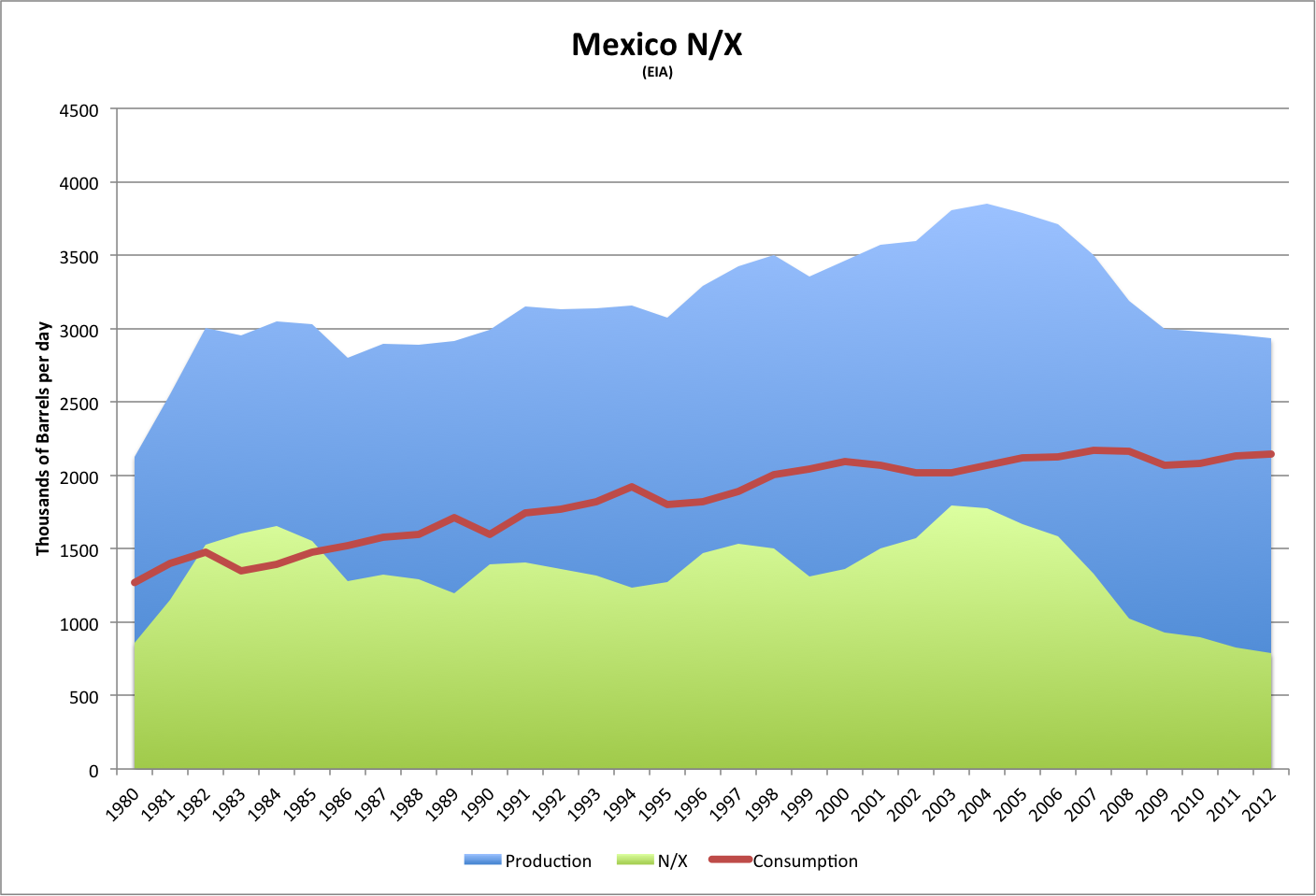

Thus, the following graph of Net Exports reveals the potential onset of the phenomenon described by Jeffery Brown as the Export Land Model (I need to discuss this in a post) where we see how quickly countries can swing from exporters to importers in the presence of rising domestic consumption and declining production (Indonesia, Malaysia, Egypt, Vietnam come to mind).

These trends need to be remedied before Mexican oil starts having a material impact on global markets. A booming Mexican economy is likely to continue it's increasing consumption trend; thus increasing exports requires: arresting the current production decline trend, find enough new production to offset demand increases, and finally to push production growth beyond demand growth.

Regardless of the plausibility of this or your political opinions on the reform, it seems to be widely acknowledged that Pemex needs a re-think. The state bleeds Pemex dry (via royalties and taxes). It's bound to it's loss making refining industry. It's corrupt. It's unproductive. It lacks current technology. It's racked up huge sums of debt. All of these issues are low hanging fruit to pick, and whose presence actually increases the chances of a production turn around (if addressed).

Regardless of the plausibility of this or your political opinions on the reform, it seems to be widely acknowledged that Pemex needs a re-think. The state bleeds Pemex dry (via royalties and taxes). It's bound to it's loss making refining industry. It's corrupt. It's unproductive. It lacks current technology. It's racked up huge sums of debt. All of these issues are low hanging fruit to pick, and whose presence actually increases the chances of a production turn around (if addressed).

Here's an excerpt from an article run in the Economist this summer:

Its first problem is structural: it has never been treated as a profit-making company. Astonishingly for a monopoly that drills every barrel of oil in Mexico at an average cost of less than $7, and sells it for around $100, it lost an accumulated 360 billion pesos, or $29 billion, in the five years to 2012 (despite a small profit last year). This is partly because although its oil-and-gas-production side makes a fat profit, its refining business loses a fortune, and its petrochemicals division is also loss-making. Worse, the government sucks out cash to compensate for the lack of tax revenues it collects in the rest of the economy. Last year 55% of Pemex’s revenues went in royalties and taxes. This perpetual drain on its cashflow means its debt has soared to $60 billion. The hole in its pension reserve is a whopping $100 billion.From a Brookings Institute report:

However, national pride in the ownership of its “black gold” requires an extensive education campaign; and Mexican citizens deserve an honest assessment of their depleted national asset. PEMEX is both an emblem of the nation’s wealth and a behemoth riddled with corruption. Under PEMEX, yields from Cantarell, the principal oil field, have diminished and Mexican oil and gas production has fallen from its apogee in 2005 of 3.425 million bpd to 2.548 million bpd in 2012. Instead of using PEMEX revenues to invest in new exploration, technology and maintenance, these funds are diverted to supporting approximately one third of Mexican government expenditures. Currently PEMEX only reinvests 15 percent of its total portfolio in exploration activities, far below the level of Brazil’s PETROBRAS and its other international competitors. We may conclude that PEMEX fails to act as a for-profit corporation, but accepts the role as a government agency which profits are invested in the state’s social and infrastructure programs, thus relieving Mexican citizens of paying high taxes.If you want to increase oil production, invest in oil exploration and production. Seems simple enough... right?

What is the Potential?

We'll have to see how things shake out politically. But it's not hard to imagine that all of the big players will be on the doorstep waiting to get in. The wildcard will be the political climate. Assuming that gets sorted out, we're left with some pretty favorable circumstances.The geographical similarities between Mexico's tight oil and deepwater plays and the corresponding American plays should reduce the operational risks and allow Pemex to import known, successful, technologies. With prospective deepwater barrels of 26.6 billion barrels and over 60 billion barrels on shore true liberalization would be a feeding frenzy.

From this Bloomberg article:

Mexico is the world’s ninth-largest oil producer, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, and possesses the biggest unexplored crude area after the Arctic Circle. Industry analysts and the bill’s authors say the overhaul will reverse eight years of oil output declines for Petroleos Mexicanos and increase production to as much as 4 million barrels per day by 2025. The plan would change the constitution to allow production sharing and licenses for outside companies that will also be able to log crude reserves for accounting purposes.

“With reform there will undoubtedly be a spurt of production growth as Mexico is a very rich hydrocarbon area both onshore and offshore,” Ed Morse, the New York-based head of commodities research at Citigroup Inc., said in a phone interview before the vote. “Realistically, it could double the amount of oil that Mexico produces.”While this seems awfully optimistic, at the very least we can say the potential is huge. But people are assuming a pretty liberal interpretation of these vague amendments. Until they are finalized and are put into operation we won't truly know.

Political Ramifications.

Well, there's this guy:Newsweek ran a story discussing some of the potential political roadblocks:

Left-wing legislators say they have enough signatures to challenge Peña Nieta’s new law, and according to polls up to 60 percent of Mexicans would vote it down in a referendum. A former left-wing presidential candidate, Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, recently wrote a letter to several of the big oil companies, warning them that if the public votes the oil reforms down, foreigners would lose any investment they had made in Mexico until that time.Remember, Pemex has been subsidizing the state to a significant degree. This article by Reuters compares these rates to other state owned companies:

Last year, Pemex paid $69.4 billion in taxes on $69.6 billion in pretax profits, a 99.7 percent tax rate.

That compares with rates of 69 percent for Venezuelan state-owned oil company PDVSA, 25 percent for Brazil's Petrobras and 31 percent for Royal Dutch Shell Plc, according to the companies' 2012 annual reportA reduction in subsidies coinciding with the inevitable 'Big Oil' profits is a populist rallying cry if I've ever heard one. While I'd certainly make the case that the long game of this, the increased productivity and foreign direct investment (FDI) will likely prove superior to the status-quo alternative (in production, economic and social terms), populism and politics don't always have the patience or motivation to hear that case out.

I also wonder about the public image of the traditional 'big oil' players in Mexico. Is all FDI viewed the same? Are some foreign entities better equipped to make the concessions necessary to give Mexican politicians a sellable option to put in front of a skeptical populace?

Constructing a Sellable Solution.

Big oil is bad, more jobs is good, reliance on product imports is bad, domestic refining is good... how might these items shape the discussion going forward?

Mexico's inability to refine adequate amounts of it's crude oil, while still exporting raw oil to the American refinery products (the refining capacity of Padd III described here) presents some interesting options for Mexico. The EIA graphs this trend here:

Mexico's inability to refine adequate amounts of it's crude oil, while still exporting raw oil to the American refinery products (the refining capacity of Padd III described here) presents some interesting options for Mexico. The EIA graphs this trend here:

If only Mexico could find a country with a bunch of patient money, the willingness to offer affordable joint-ventures, and the technical capability to build world class refineries...

I guess Reuters did report earlier this year that Pemex would begin shipping 30,000 bopd to China. And mentioned (unfortunately, specifics are hard to come by):

Pena Nieto and Pemex signed two separate agreements with Xinxing Cathay International Group and China National Petroleum Company for academic and technological cooperation.

And in September the South China Morning Post did report that some infrastructure deals were on the table:

As one example of a Mexican project seeking Chinese investment, Pemex, the state oil monopoly, will require 52 oil platforms in the Gulf of Mexico in the next six years. Each platform would cost about US$280 million, Moreno said.

Other projects for which Chinese investment was being sought were three railway lines with a total cost of US$2 billion to US$2.5 billion to be completed within six years.

Mexico also required large investments in the renovation of two ports and the construction of a new port, Moreno added.

"The Mexican government wants to upgrade ports," he said. "Chinese technology is very state-of-the-art."

Earlier this year, Mexican President Enrique Pena Nieto announced a transport and communications infrastructure investment programme for the six years to 2018, under which the government would allocate US$300 billion for building highways, railway, ports, airports and telecommunications infrastructure.

Pena Nieto also announced the opening of opportunities for foreign investment in energy and mining, which were previously closed to foreign investment.

"There is greater possibility of Chinese companies investing in Mexican oil," Moreno said.

Conclusion.

At the end of the day, any new potential production is not good for Alberta, but I believe is good for the world (yes I'm saying that alleviating the energy poverty that exists in most of the world outweighs the impact on global warming that this production will have).

How these reforms look after they work their way through the political and legal process remains to be seen; and we probably won't be able to make a judgment on them for quite some time.

All of the big players will be at the table on this one (unlike the recent Sub-Salt auctions in Brazil) but I wouldn't be surprised to see some very big China-Mexico JV, partnerships, and agreements in the near future (yes I realize I'm seeing alot of things through this lense as of late; so take it for what it's worth).

No comments:

Post a Comment